A Centaurian can't hibernate safely forever. Even a hibernating cold-blooded metabolism isn't completely lifeless. Every five months onboard time, Torra Zorra's chamber slowly warmed, and the 130-centimeter creature recovered and replenished itself.

The first time, before awakening Torra, the S.I. had courteously reduced thrust from their cruising acceleration of 2g to the comfortable 0.5g of Torra's home. It had made the excursion almost pleasant, to say nothing of offering a unique opportunity to use its wheels the way evolution had intended. Torra had rolled itself out onto the thrust floor, stretching its four arms 'til all the stiffness had vanished. It made a line straight for the food stores and shoveled handful after handful of oood(v)(r)uut(l) into its mouths, washing it down with enough salt water to fill all four of its stomachs. Then came a leisurely couple hours of scanning its compatriots' coffins; exercising its arms, legs, and foot wheels; and checking the instruments to make sure the S.I. hadn't missed any comeuppances (it hadn't). They were right on schedule, having burned through over half their antihydrogen fuel, and their speed had reached an impressive — but expected — seven-tenths of the speed of light.

It would have been futile to look for messages from home at this early date, though. Sure, the HCDF knew their mission profile well enough that they could predict their precise position in space at any time, and thus could tight-beam signals directly at where they were. XRCP meant that such signals would be more than clear enough, and powerful enough, for Mercurand's UV receivers to pick up and decode. But even though they'd only been en route for five months, their initial transits through two hyper holes had put them over seven light-years away from Human-Centauri. Any signals beamed to their anticipated position still had to lumber through space at the speed of light, so they wouldn't be able to intercept such signals for at least another six years, probably more. Torra had glanced once at the empty message queue — just in case its hopes for news of home had somehow broken the laws of physics — and then rolled back to its refrigerator, sealed the door, and started the next five months of deep sleep.

The second time, Torra floated out into null gravity. They'd reached their top speed of 920 permil a month ago and were now on the long coasting phase. That, Torra had expected. What Torra hadn't expected was for Captain Tractor to be floating right there in the same room.

"Ken?" Torra Zorra rubbed the last traces of hibernation from one groggy eye stalk. Ken was awake? Had something gone wrong with the humans' SMS chambers? Had there been a spacecraft malfunction that the S.I. couldn't handle? They couldn't be there at UV Ceti after only 10 months onboard time, could they?

Ken Tractor grinned with a meaning Torra couldn't fathom. "I woke up early because I want to show you something. Something very few humans or Centaurians ever get to see."

"Well, what is it?" Torra asked.

"Follow me," Ken said. He brachiated out into the exit corridor.

Torra hated it when humans got all enigmatic like this. All it could do was follow the Captain and hope that whatever surprise he had in store, it wouldn't hurt much. "Did you wake up the Colonel, too?"

"I . . . didn't want to disrupt her SMS," Ken said.

Out in the hallway, Ken took an unexpected turn toward Mercurand's outer hull. Torra had never had occasion to venture into this part of the starship before, even during the walkaround back on Human-Centauri III. The "thrust floor" and "braking floor" markings adorning the walls twisted sharply every time the corridor made a right-angle bend. The handholds presented their own set of problems. Though they were on an HCDF mission, this starship was originally intended to transport civilians, and civilians came in all stripes and all levels of experience, from the century-old spacers whom time dilation and SMS had kept young and spry to the neophyte who'd never been on a spacecraft before in his life. The newbies had a tendency to settle into their normal walking gait whenever the craft's thrust or braking provided them with a "down" direction, which meant they weren't expecting things like handholds to suddenly appear in their path when they turned a corner. After the first few complaints about "tripping over these damned things," it became custom on civilian spacecraft to never put a handhold on any surface that could serve as a floor when the vessel was underway.

Mercurand's designers had gotten rather . . . creative when it came to following the letter of that custom. Some of the handholds were so far apart that it was impossible to reach one while still holding onto another; in other places, the handholds had been crammed close enough together to serve as a ladder while the starship was thrusting or braking. Switching handholds when brachiating through those sharp twists and turns was a challenge, often requiring some serious planning ahead from both of them.

Ken stopped abrutly at one of these ladders, which ended a few meters farther out at an open hatch. "Here we are," he pointed outward through the hatch. "Mercurand's one-and-only observation bubble. Go out and take a look."

"At what?" the Centaurian asked.

Though Torra couldn't read Ken's expression, he was looking positively smug. "At the universe at ninety-two percent of the speed of light."

Now Torra was intrigued. It pulled itself through the hatch into the short access tunnel beyond. Even though they were in zero gravity, millions of years of evolution climbing the cliffs on Go'orla meant there was one, instinctive way for a Centaurian to proceed: it "climbed up" the handhold ladder with one eye stalk craned above, one eye pointed at the wall, and the third eye scanning the area below its feet. The last, in case any wild predators should approach from below, of course. That topmost, craned eye could see the glimmer of stars directly above — or directly ahead, depending on which direction one wanted to call "up" at the moment — but there was something . . . off about them.

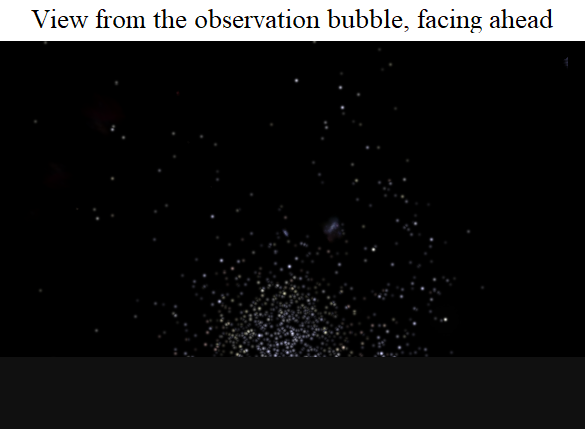

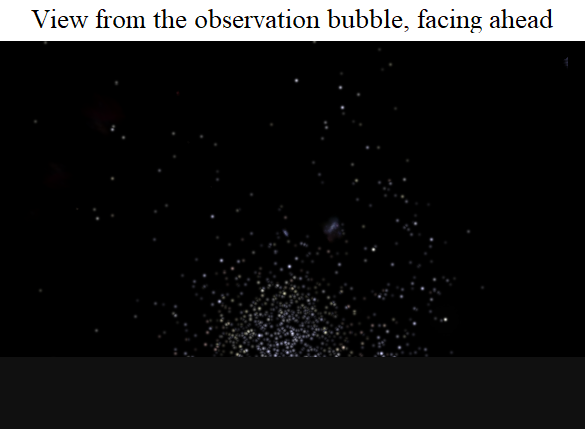

As Torra slowly pulled itself nearer to the window, and it grew larger in its field of view, the problem with the stars became obvious. There were far fewer of them than there had any right to be. And the few stars that were visible were clustered all to one side of the window. It only took Torra a second or two to piece it together. At the speed a starship travelled, it had to keep its nose pointed in the direction of travel for most of the journey; the collectors there were the only way to keep the onrushing interstellar medium from slashing through parts of the spacecraft it shouldn't. This meant Torra was now staring out sideways, at an angle perpendicular to their course. Torra glanced at the "thrust floor" and "braking floor" markings to make sure; yes, the side of the window toward the front of the spacecraft was the side with the stars.

Torra finally pulled itself all the way into the observation bubble, a plexiglass canopy not much bigger around than its own body. And when it realigned all three of its eyestalks in their usual 360-degree ring, the full, spectacular panorama struck with all the awe and wonder of Creation.

Mercurand's own hull cut the view in half. Like standing on a tiny, tiny planet, the gloss-black starship hull produced its own horizon line. Only the hemisphere above Torra's eye stalk was open to view. But what a strange and wonderful hemisphere of stars it was! Nearly all the stars lay clustered ahead of the starship, like a vast sun setting over the forward horizon. That was the stellar aberration. They were streaking toward and through the light sources nearly as fast as their photons were headed toward them. Like running through a rain shower, when the vertical raindrops appear to be slanting down upon you at an angle, so the photons looked to be coming from a different direction than they actually were.

And the effect wasn't uniform. Dead center ahead of them should have been the constellation of Cetus the whale, but Torra couldn't make it out. For one, the stars were squeezed too close together. For another, a little ways off from the center, those same constellations were squeezed a little less tightly. The overall effect was like a funhouse mirror, or a pattern stretched in different directions on a lump of silicone bouncing putty. Even if Torra could have recognized the squished star patterns in the center, their progressively wonkier distortion the farther from the center Torra looked rendered them utterly unrecognizable.

The stars also looked a little . . . bluer than they should have been. That was the blueshift. At 920 permil, the light from those stars directly ahead had 4.9 times its normal frequency. Even ordinary red light was shifted well up into the ultraviolet. The light Torra could see from those frontmost stars had started out way down in the infrared, shifted to visible only because Mercurand — and the three passengers aboard it — were charging toward them at such a monstrous pace. A few degrees off from directly ahead, the stars were still the blue-white color of the hottest blackbodies, but now it was a higher-frequency portion of their original infrared light that Torra was seeing.

The effect would have been even more pronounced had Centaurian eyes posessed the red and green cones of human ones. As far as color sensitvity went, the backs of Torra's eye stalks — the surfaces that served as its "retinae" — had only an analog to a human's blue cones. But they also posessed a kind of full-spectrum light-sensitive cells similar to, and far surpassing, a human's "rods." These rod-analogs could operate equally well in both dim and bright light, had an almost uniform frequency sensitivity, and produced an image every bit as sharp as a human's daylight vision. The whole picture painted by a Centaurian brain's vision center was like a well-focused black-and-white photograph, onto which various intensities of blue had been overlaid. This combination of super-rods and blue cones had been enough to allow its ancestors to survive the plains of Go'orla for millions of years, and they were also enough for Torra to tell the difference between normal stars and these overly-blue pinpricks of light shining in from straight ahead.

Outside that central disc dead-ahead, about 20 or 25 degrees away, the stars looked more normal. Some were bluer, some less so, and most were the neutral white that marked a normal night sky. But farther off, more than about 25 degrees to one side, the stars appeared less blue than they should have. A human like Ken, with his tri-color retinas, would have called them "red," or at least a dull "pinkish." And as they grew progressively less and less blue the farther away from dead-ahead Torra looked, they also grew dimmer. That was emission aberration, part of the "beaming" effect — moving directly toward a light source meant you were running into more of the emitted photons every second, while moving directly away meant the photons would be more spread out in time.

At 92 percent of the speed of light, as Torra was travelling now, the beaming effect combined with the redshift to render all stars behind them invisible to the naked eye. Even Sol, which was a hair less than a light-year to their rear and should have appeared brighter than any other star in the sky, was nowhere to be seen.

And in actuality, at this speed, Sol was a lot closer even than that. Sure, to an observer standing still in the Sol system, Mercurand was almost a light-year away; but from Torra's vantage point on Mercurand itself, Sol was barely a third of a light-year behind them. Every student of special relativity knew that fast-moving objects shrank in the direction of motion, an effect called the Lorentz-FitzGerald contraction, but it was easy to forget that this effect was mutual. From Torra's perspective, Mercurand was standing still, and the rest of the universe was whizzing past at 920 permil. That meant the universe, and everything in it, was shorter in the direction they were travelling. And it didn't just appear this way, the universe really was physically shorter. Sol wasn't 0.92 light-years behind, as 9 months of accelerating at 2g and one month of coasting should instinctively have rendered it — it was only 0.36 light-years behind. UV Ceti wasn't still 7.63 light-years ahead of them, it was only 3 light-years ahead. This played into the already-distorted shapes of the constellations to Mercurand's front, making them even more distorted still.

It was as though a black tunnel had been stretched around them, and the light at the metaphorical end of the tunnel was the light of every star. A light which, brightest and bluest at its center, lay before them like a pale, speckled, rainbow-colored archery target. And this state of squished reality would continue until Mercurand started to put on the brakes two-and-three-quarters years from now. Or rather, two-and-three-quarters years onboard, with time dilation speeding things along. It wouldn't happen for seven-and-a-half years by the clocks in the rest of the universe. (Or was that one-and-one-sixth years for the rest of the universe? Time dilation played havoc with the mutual nature of relativity even worse than the Lorentz-FitzGerald contraction did, and Torra could never keep up with all of it. Though Torra did realize that time dilation precisely cancelled out the effect the Lorentz FitzGerald contraction would have otherwise had on how bright the stars ahead appeared.)

Torra craned all three eye stalks forward, staring intently at the unchanging view to the front. It wanted to stare for hours, to absorb as much as it could of this once-in-a-lifetime glimpse at the relativistic universe. To stand, or lay, suspended in this world-between-worlds-between-worlds and drink of its majesty and serenity forever.

But it also knew that Mercurand's forward-sweeping UV laser and electrostatic scoop weren't perfect, and couldn't intercept every atom or ion of interstellar hydrogen. Plowing through the not-quite-vacuum between the stars at ninety-two percent of light speed meant that every second, a few of these subatomic bullets were making it through their electrostatic safety net and streaking alongside — or directly into — Mercurand's hull. The transparent observation bubble Torra now occupied offered little to no protection, when compared with the particle shielding lining the hull. So, with a military spacer's discipline, Torra pushed itself back in along the ladder, one rung at a time.

Back inside, Ken was waiting. "Well," he said, "Given how long you spent out there in the observation bubble, I'm guessing the view was worth it."

"It was," Torra said. "For a few moments, I could forget all about the reason we're going to UV Ceti. No ghost, no ten year deadline, no 'everything will end,' just . . ." It tilted away in a Centaurian shrug. ". . . serenity. The whole universe, turned into a pancake. All the petty little worries of living and fitting in and fighting wars, all of it compacted into that disc of stars, so far away and rushing by so fast that none of it mattered at all."

Torra's voice dropped to a near whisper. "And . . and then I think about my clan. And suddenly, the reason we're out here does matter. Heck, they're why I joined the HCDF to begin with. Not Human-Centauri, not the Emotional Plague, them. I don't know what Arnold meant by 'everything will end,' but I do know that I don't want Clan Zorra to end with it."

Ken blinked a couple of times, just a little uncomfortably. "Sometimes, I envy the depth with which you Centaurians care about your families."

"A clan's more than just a family," Torra explained. "Even the word clan doesn't really do it justice. It's a miniature society, bound together by emotional ties every bit as strong as how you humans feel toward your mates. Within a clan, there's an absolutely equitable division of labor and hardly any interpersonal strife, with no leaders and no pecking order. From each according to its ability, to each according to its need."

Ken frowned. "And it works?"

Torra seemed puzzled for a moment. "Of course it works. It's a natural instinct. Why wouldn't it work?"

Ken said, "We tried something similar, in the distant past before First Contact. It was called communism. It utterly failed to work with any group larger than about a hundred people. Every attempt to make it work on a national level turned into a brutal, impoverished dictatorship."

Torra said, "Well of course it won't work on the scale of an entire civilization. Clans require intimacy. They can't get bigger than about fifty Centaurians. Any more than that and a clan'll come apart at the seams. One of our . . . ancient legends — from before we started digging into our past with real archaeology and paleontology — talks about a mythical "first clan" that got too big and splintered. According to that myth, all the ills of Go'orla stem from that moment; every war, every case of slavery, every —"

Ken interrupted. "Wait, slavery?"

"Yeah," Torra replied. "Clans used to own other clans as slaves. The practice wasn't abolished until less than a millennium ago. We like to pretend that in Human-Centauri, all clans are equal, but we all know that isn't even remotely true. Even with QC&C fusion and assembly bots meeting every conceivable need, each clan still vies with every other clan, for power and for status and for the biggest share of the pie it can get. It's only because they'd have so much to lose that these rivalries remain civil. If somehow the machinery of civilization were to fail, and heat and shelter and living space were to get scarce again, we'd be looking at civil war, or worse. Every clan would feel threatened by every other clan, and all too many of them would respond to this perceived threat by attacking first. There are plenty of examples from history where a once-mighty empire descended into every-clan-for-itself savagery."

Ken nodded. "We have an old saying. Every society is only three meals away from revolution."

"Three meals?" Torra puzzled. "Oh, right. I'd forgotten how essential a large food supply must be to you humans. You do eat an awful lot."

Ken shrugged. "Being warm-blooded has its cost. But it has its advantages too. In a cold environment, we can just put on a coat or a blanket, no portable heaters necessary."

"So you can starve to death in any weather," Torra said.

"Hah!" Ken gave a good, hearty chuckle.

"Speaking of meals," Torra began, "I haven't eaten in five months." It paused. Clan-away-from-clan or not, there was a certain Centaurian intimacy to what it wanted to ask next. "Do . . . do you want to go have food together again?"

The Pentagon War is continued in chapter

12.

Roger M. Wilcox's Homepage